Social media has an interesting way of making you aware of things that, while it seems like common sense to you, appears to be a hair-triggering, spittle-making, absolutely bonkers debate to others. Today’s subject is on the concept of gatekeeping… Fabric.

Yeah, fabric.

Let’s start at the beginning. On Instagram user @alateish (aka Alatheia) shares screenshots from an 18th century sale-buy group on Facebook, shaming someone for selling a pair of silk polyester breeches for an affordable price. They go on to say that shaming someone for making beautiful objects out of poly or rayon blends is not helpful, and not everyone can afford natural fibers. This sentiment is also voiced by other 18th century costumers, which are also voiced by historical costumers, re-creators, cosplayers and hobbyists, and eventually it lands in my feed and it has me going “Who’s got the time and energy to belittle fabric choices?” It turns out, a good amount of people do.

Social media also has an interesting way of magnifying on an issue that, while appears to be short lived and petty, stems from a deeper root of systemic issues and (particularly to historical costuming) a community’s inability to regulate themselves and adapt for growth and change.

Here’s a reason why shaming someone for their fabric choices is not helpful: the availability of fabric is a geo-political hot button. Yes, fabric has ties to politics and we shan’t ignore it in this blog. It is extra disappointing to shame others for fabric choices when it’s a documented case that costs and accessibility to fabric is a tale as old as time.

An example from The Tudor Tailor:

“People strove to wear the best they could afford …. Christmas expenses for the Lestrange Family in 1519 serve to illustrate purchasing power at the beginning of the [16th] century. A day’s wage for a laborer would buy a yard of the cheapest cloth (canvas at 4d a yard), while his wages for six months would barely buy a yard of the dearest (cloth of gold at 58s 8d a yard), and a fine cloak, at £20, would require more than 3 years labor.” (Ninya Mikhaila & Jane Malcolm-Davies, The Tudor Tailor, Chapter 4, pg. 35)

This principal still applies to us in the 21st century. What is affordable to an American is widely different than to those in South America or Eastern Europe. While an American on median wages may be able to afford limited supplies of “100% natural fibers” these gatekeepers covet so, such cannot be said of clothing counterparts in Lithuania or in parts of Brazil. In fact, linen or broadcloths may not be available due to the sheer demand of clothing factories for general production in mainland Asia or consumers in Canada. In fact, the reason why parts of the western world is even able to provide natural fabrics to the retail market is can be attributed to the existence of rayon and polyester in the industrial market.

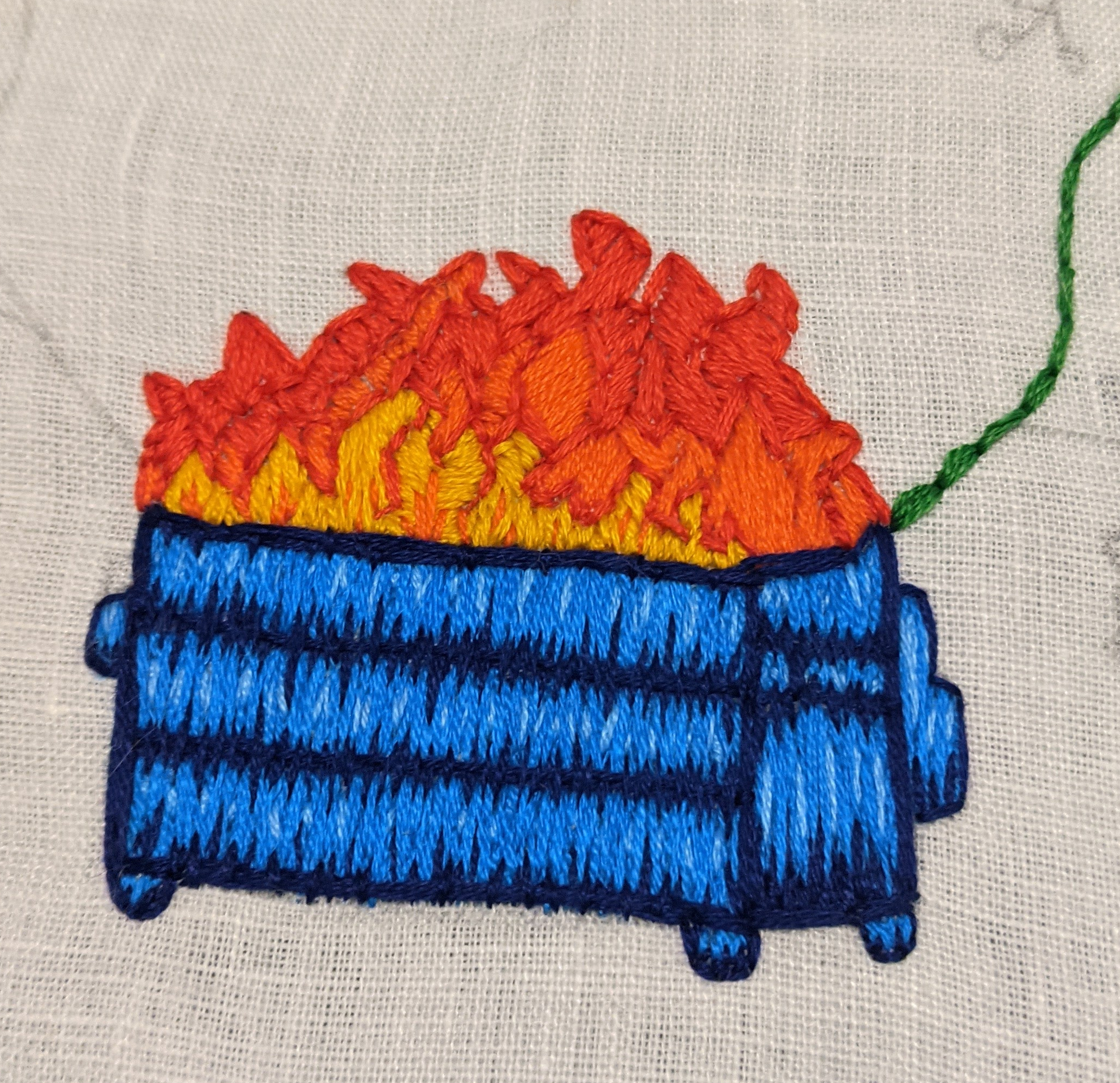

To create a fictional gate in which to filter tailors, stitchers, cosplayers, and historical interpreters on the arbitrary standard of “natural fibers” continues to reinforce the systemic issues of class, race, and disability status. The other side of this coin is that once all members who do not adhere to this standard, when they are finally gone, the steadfast guardians of such an ostentatious gate will then turn and build a new one; such is the self-fulling prophecy of gatekeeping and it’s ultimate result: the death of a community.

The most interesting facet of watching this play out on social media is the refreshing accountability held by prominent members of their communities. Dr. Christine Millar (aka Sewstine) makes the concise point that in order for fabric companies to continue creating reproductions of historical fabric they must produce them as either rayon blends or polyester blends, and if anything are entirely synthetic.

Even Zack of Pinsent Tailoring discusses his personal use of synthetic material in the early days of his tailoring career, adding the asterisk that while he makes the personal choice to seek and use natural fibers for environmental purposes, Zack has no plans to shame anyone for doing otherwise. Watching respected members of their communities to speak about their experiences with fabric and creating give us a common thread: that gatekeeping as a principal is not acceptable and that we must do better.

These “Fabric Wars”, as it has been coined, being the hydra of community bane, what can we as makers do?

The philosophy is simple, if difficult to execute: be the change you want to see. Reach out to people to share resources such as academic papers, textile providers, sewing techniques to maximize fabric use. Educate others on the specific purposes of each fabric and how to utilize it to the best of their abilities. Discuss the impact the fabric industry has in your area. Write to your retail providers with feedback, or write to your representatives and voice your needs. If you cannot be the change you want to see, all you’ll end up finding are gates and their keepers.

Let’s see how this “Fabric War” plays out on social media.